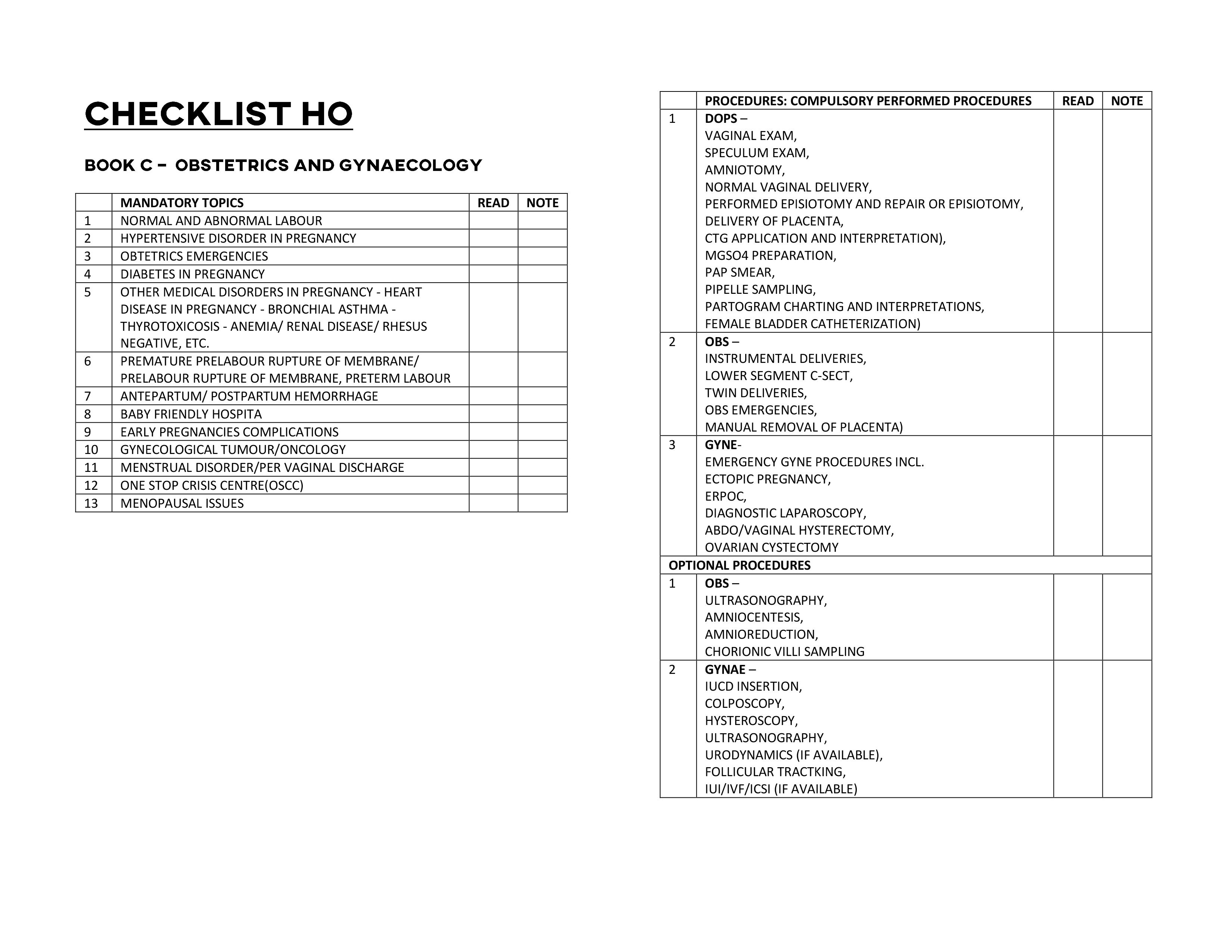

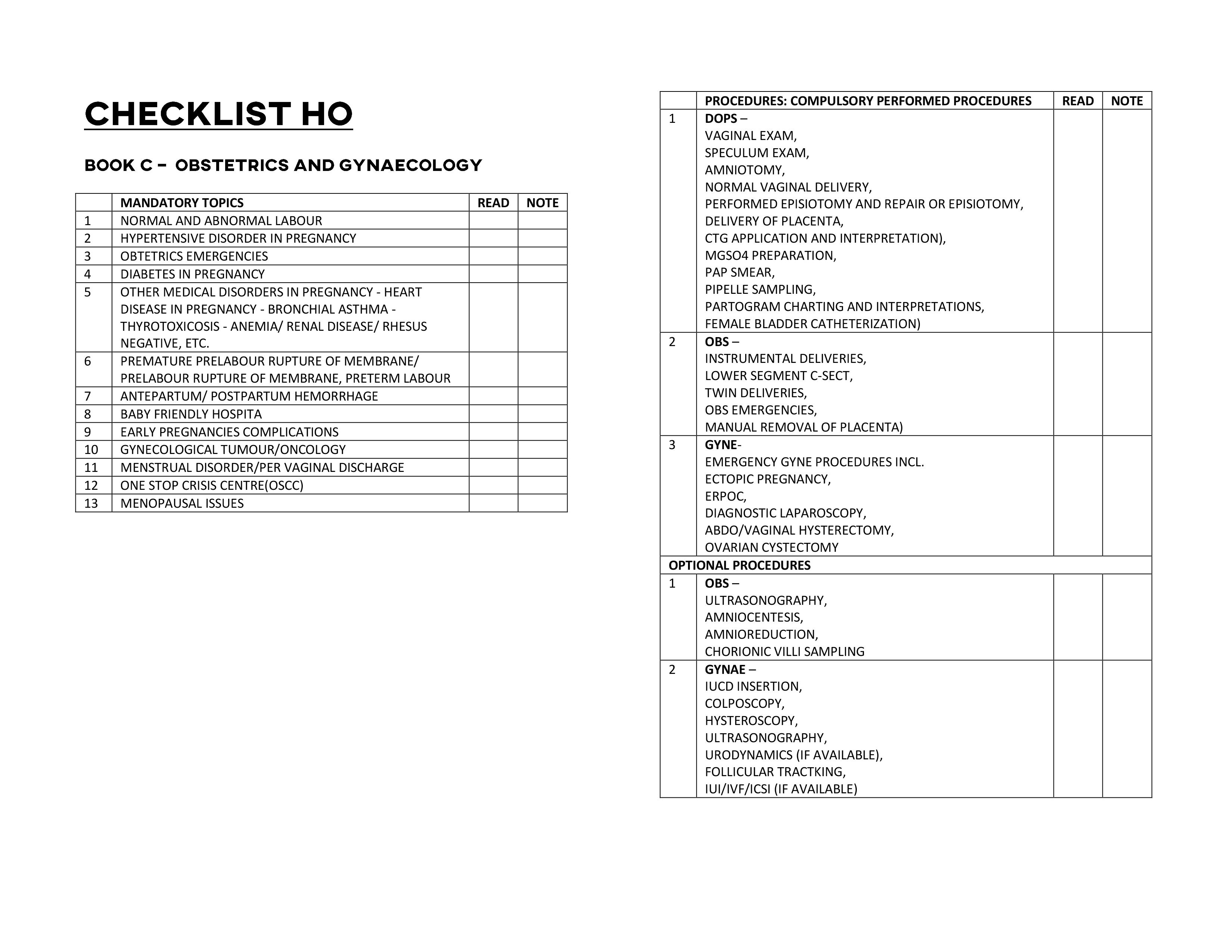

Here is the compilation of topics and procedures in the housemen logbook.

Plan your long waiting time well. It could take at least 8-12 months until your housemenship.

You’re welcome

CLICK down below for the pdf file

Here is the compilation of topics and procedures in the housemen logbook.

Plan your long waiting time well. It could take at least 8-12 months until your housemenship.

You’re welcome

CLICK down below for the pdf file

[C&P]

I will say that 90% of a doctor’s job is to talk. We present cases, do referral, talk to seniors, teach the juniors, asking help from nurses/PPK, explain to patients. We talk all the time!

Communication is very pertinent in this line of work. The management for any patients starts with a clerking and case presentation. This is the most important part of working as a doctor.

Honestly, almost every day is a headache for me listening to my HO presenting cases in the ward. I’ve been meaning to write something about it. I really want to help them so here it is. The step-by-step guide for a good case presentation.

STEP 1: REASON FOR ADMISSION

The most important puzzle that you need to solve for each clerking is why do patients need the admission. You figure this out and trust me, half of your presentation is already done.

The current diagnosis may not be the reason why patient is being admitted. Patient may be treated as gastritis now, but the initial reason for admission may be to rule out pancreatitis. It is weird to admit patient for a disease that can be managed as outpatient. Tell us the reason for admission first, not throw away the current diagnosis in your first sentence.

Similarly, when patient is electively admitted for an imaging study, find out the reason why. Because why do we have to waste a bed for a procedure that can be done as outpatient.

Find out if patient is admitted from Emergency department or a referral from other hospital/clinic. Find out who receive the referral or who admit the patient. Don’t be surprise when the reason can be as simple as admitted by specialist/consultant because the patient is his/her friend!

Then for each admission, justify if it is necessary. Don’t just clerk, examine patient, write endlessly in the case note, and worse, inserting branula and sending blood specimens for investigation when in the end, the admission ends up being cancelled.

Similarly, if patient is not discharged when they are supposed to, also find out why. When post appendicectomy patient being kept for 5 days, there must be a reason for it.

Find out why your patients deserve those hospital beds, or still need to be on it instead of going home. Solve this puzzle first and you are already half way there.

STEP 2: OPENING STATEMENT

“50-year-old Malay gentleman. No known medical illness.”

“62-year-old Chinese lady. Known case of hypertension and diabetes mellitus under polyclinic follow up.”

“25-year-old Iban lady, gravida 2 para 1 at 32 weeks POA/POG.”

“4-year-old boy with underlying acute lymphoblastic leukemia.”

Every department has its expected opening statement. The script is almost the same for all patients. Know the pattern and after a while, it will become natural to you. Know which is important, what to say and what not to say. You do not have to list all the known medical illnesses. Tally it to the person you are talking to at that particular moment.

A surgeon may not be particularly interested about medical history in details, so enough just by stating that patient has underlying relevant medical illness and then go straight to the REASON FOR ADMISSION. However, if patient is on anti-platelet or anti-coagulant, you may want to say it briefly in your opening statement because a surgeon would want to hear that.

Similarly, a physician wouldn’t want to hear in details about history of laparotomy 20 years ago when the reason you talk to him/her is only for uncontrolled hypertension. A gynaecologist also will not be interested to hear about history of gout when the reason for referral is prolonged menses.

Recognize who you are talking to! Anticipate their questions and provide the answers before they even ask!

STEP 3: THE USUAL STEPS

History, physical examination, investigations, diagnosis and management. We have been taught about this since medical school. Follow this and you will never go wrong. But….

There are two circumstances how this pans out.

If you are the first person clerking the patient, you have to sell your diagnosis and management plan. This usually happens for a new admission with no definite diagnosis yet. So you have to follow the “medical school” steps up there.

For example, “20-year-old Malay guy, no known medical illness, admitted from ETD for acute appendicitis. He presented with 3-day history of RIF pain, associated with fever, loss of appetite and passing loose stool. There is no UTI symptom. Clinically, not septic, not dehydrated. Abdomen is soft, tenderness at RIF, no mass palpable. Hernia orifice is intact and both scrotum and testis are normal. TWC is 15,000 and UFEME is negative for UTI. My clinical diagnosis is acute appendicitis. I’m keeping him nil by mouth with IV fluid. I plan to start antibiotic and post for appendicectomy.”

Another example would be, “20-year-old Malay guy, no known medical illness, admitted from ETD for acute appendicitis. He presented with 3-day history of RIF pain, associated with fever. However, patient also complained of UTI symptoms. Appetite remain good and bowel habit was normal. Clinically, not septic, not dehydrated. Abdomen is soft, very mild tenderness at RIF, no mass palpable but the right renal punch is positive. Hernia orifice is intact and both scrotum and testis are normal. TWC is 15,000 and UFEME shows presence of leukocyte and nitrites. I don’t agree with ETD diagnosis of acute appendicitis. I think he has right pyelonephritis. I plan to allow him orally, send for urine C&S, start antibiotic and observe his symptoms. I am requesting a KUB x-ray to rule out renal calculi, KIV for USG.”

The second situation, on the other hand, is rather easier and you encounter this daily during morning round. Most of the patients have been admitted for few days. Diagnosis has been made and management has been laid out by specialists and even consultants. You don’t have to crack your head selling the diagnosis. Just tell us the diagnosis and what has been done. That’s all!

The example would be, “20-year-old Malay guy, no known medical illness, admitted 2 days ago for acute appendicitis. He presented with 3-day history of RIF pain, associated with fever. Clinically, he was not septic on admission. Per abdomen tender at RIF. TWC was 15,000. Antibiotic was started and today is day 1 post laparoscopic appendicectomy. Intra op finding was inflammed appendix with healthy base. Currently patient well, ambulating, allowed orally and passing flatus. Abdomen is soft, not distended. Plan for discharge today.”

Or, “20-year-old Malay guy, no known medical illness, admitted 2 days ago initially for acute appendicitis. He presented with 3-day history of RIF pain, associated with fever. However, we figured out that patient had UTI symptoms. Per abdomen only mild tenderness at RIF but right renal punch was positive. TWC was 15,000. UFEME showed UTI picture. KUB x-ray and USG, no obvious stone seen. We treat him as acute pyelonephritis. Antibiotic was started. Urine C&S still pending. Clinically remain well and afebrile. Abdomen is soft, not distended. Plan for discharge today.”

Still I follow THE USUAL STEPS. History until management. You can never go wrong. But unfortunately, my HO always like the word CURRENTLY. The usual thing that I hear every day is “This patient is day 5 post laparotomy. CURRENTLY patient well, vital signs stable, urine output good, bla, bla, bla.”

Ask what is the diagnosis, they vomit out the documented post-operative diagnosis. Ask why laparotomy was decided, I get blank stare. Ask can patient be discharged since all the CURRENTLY seems good, another blank stare. Ask why patient is still in acute cubicle, continuous blank stare. The fact that patient was in hypovolemic shock on admission and intubated in ICU, no one knows.

Patient is not just managed for a day. Not only during the day that you review the patient. Management starts from the first clerking until you give the discharge plan. Understand those and trust me, you will be surprised on how fluent you are telling the story of your patients.

Read again all my examples above and time yourself. See how long do you take to present a case. Less than a minute!! It is not that difficult. But if you still think it is, go to the next step!

STEP 4: REPEAT ALL THE STEPS

It is about practice and practice. Do it again and again and again. No one can miraculously get it right the first time. Not even your consultants now. We all start somewhere. The question is, do you want to start? If you keep quiet and hide behind others all the time, how do you expect to present well? If you don’t force yourself to be brave, making mistake and take the occasional scolding, you will never improve.

I started doing this, or rather being forced to do it, during medical school. I remember as a 3rd year medical student in O&G posting that I am not allowed to sit for my end of posting exam and be considered non-redeemable fail, if I do not perform a total of 10 case presentations. I remember that as a group of 10 students in General Surgery, we have to know ALL patients in the ward. God forbid, our lecturer picked a patient in the ward for bedside teaching that no one clerked. Because that means we will be chased out from the ward. By the time I was in final year, I was so tired of presenting cases that I said to myself, just give me the professional exam and be done with it. So I can start working and earn money because I was doing a HO job anyway. Might as well be paid doing it. 😀

So seeing HO now struggling to present and refer cases, to even communicate with others, of course I feel frustrated and sad at the same time. But then again, like I said, we all start somewhere. I will always be around to help and to guide. The question is, do you want to start?

Credit to : FB Aimir Ma’rof

[C&P]

I have been listening to the case presentation by medical students ever since I started working here. After many years of working with house officers, I admit the feeling was totally different. I think because of the intent of the presentation. One is for teaching purpose to pass an exam, while the other is for working purpose to manage patients.

So yes, I get confused initially on how to teach them. But after few days of “acclimatization”, I am writing this hoping that it can serve those two purposes simultaneously. I hope you will find it beneficial because the ultimate goal is still the same i.e. to be a safe doctor and to manage your patients well.

STEP 1: PRE-MORBID STATUS

“Assalamu’alaikum pakcik.”

The usual stuff. We all learn this in medical school. Greet your patient well, smile and most importantly, create a quick rapport and trust. Pakcik is about to reveal everything to you. He needs to trust you.

In the first few minute, you need to quickly get the pre-morbid status. Ask about underlying medical illness(es) and the follow up. Which clinic, which hospital, government or private? Also, explore previous history of admission(s) and why. And for house officers especially, list down all current medications correctly because you need to indent them on the medication chart later.

But most importantly, you really need to ascertain the PRE-MORBID FUNCTIONAL STATUS. How is the patient before this current illness sets in? Can he/she run a marathon or easily breathless going to the toilet? Is the patient as normal as you are now, or totally bedbound at home? Anyone taking care of him/her or he/she is totally independent?

You need to establish this because the aim of management for all patients when you clerk them is the same. YOU WANT TO TREAT THEM AND BRING THEM BACK TO THEIR PRE-MORBID CONDITION. Walking or running, on a wheelchair or on a trolley, our aim remains the same for all patients i.e. to discharge them well and bring them back to their original status, if not better.

Now, here’s the catch. You don’t have forever for STEP 1. It seems like a lot to ask, but you have less than 5 minutes to do it. Because if you read my previous post on HOW TO PRESENT CASES (link below), you will know that the next step is the most important step of all. Finish your STEP 1 quickly, or skip it if you know you are wasting your time. You can come back to it later. Because here comes the most important step.

STEP 2: REASON FOR ADMISSION

The first thing you have to do is to find out whether it is an ELECTIVE or an EMERGENCY admission. Let’s look at them both separately.

ELECTIVE means patient comes for a specific reason. Someone asks them to be admitted. It can be either for surgery, for procedure, for medication, or simply, a generous favour from that “someone” (read: your boss).

It is not that difficult to clerk an elective admission. They usually come to you with a diagnosis and you just have to go retrospectively and figure out the story leading to that REASON FOR ADMISSION.

For house officers, you can dig through the previous records but for medical students, you just have to ask the history. The problem is, when your patients do not bring anything with them and say, “Entah, doktor suruh masuk hari ni, saya pun tak tahu untuk apa.” Then, you are screwed! 😁

But, trust me, there is always a way to figure that out. Di mana ada kemahuan, di situ ada jalan. Seek for the answer, and you will find it. If, you are willing to find it.

EMERGENCY, on the other hand, comes without a diagnosis. It is your job now to make up the diagnosis. This is where your medical school training comes in handy. Chief complaint, history of presenting illness, systemic review, general physical examination, focused physical examination and finally, PROVISIONAL & DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS.

A good clerking is when after 5 minutes of history taking, your mind has started listing down the PROVISIONAL & DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS. Way before you even touch the patient! This is a good clerking. You need to do a lot, I mean a lot, of clerking to achieve this. Clerking one patient per week is definitely not enough!

In the clinical years of medical school, your patients are your text book. That’s why, as a medical student, my lecturers scolded us if we didn’t clerk at least 2 patients per day. That’s why, as a medical student, my lecturers screamed at us if they see us bringing books into the ward. “If you want to read, go to the library, don’t come to the ward”, they said.

A bad clerking is when after 15 minutes of history taking, you still have not reach the diagnosis part. When you start to sweat and looking at your watch non-stop during long case examination, you know that you did not do enough during those clinical years.

STEP 3: OUTLINE YOUR MANAGEMENT

This step needs practice and experience. INVESTIGATION and TREATMENT. The more you see, the more you know.

This is where, your books will not help you much. To a certain extent, yes, but most of the time, not. This is where, the amount of time you spent in the ward, matters.

This is where, for medical students, the house officers and medical officers are your good friends. They are the go-to persons who have the explanation for every investigation and management plan.

This is where, you will see how a clinical decision making differs, from one doctor to another, and from one hospital to another. But no matter how different they are, there will always be an explanation and most importantly, the principles remain the same.

You have to know those principles. But remember, you can never reach STEP 3 if you have trouble finishing STEP 2. For medical students, trust me, the moment you finish STEP 2, you have passed your examination. If much of the question or discussion lingers at STEP 3, a pat on your back because you are a distinction candidate.

And I can assure you, if you perform well as a medical student, if you can do STEP 3 as a medical student, trust me, your housemanship will not be as bad as what is being portrayed publicly nowadays in the news. Because this is also the difference between a good and a mediocre house officer. The good ones can complete STEP 3 on their own, while the other waits for the medical officers to do it.

Which medical student are you?

Which house officer are you?

STEP 4: DISCHARGE PLAN

The biggest clerking mistake, to me, is when you clerk only for a certain period of time.

For house officers, you clerk a new admission and outline your management only up until your working shift is over. Right? Because by then, you will do passover and bye-bye, not your problem anymore. When you do a review, you only know about what happened yesterday and the next 24 hours, or up until your shift is over as well. Right?

Because if you ever work with me, you will know my favourite question to you will be, “when can patient be discharged?” It does not matter whether patient is still intubated or smiling at you. When can patient be discharged?

Similarly, medical students will clerk a patient only up until the bedside teaching is over. Right? Then, you will do the same bye-bye and if you stay around, that means the patient is your subject for case write-up. Right?

I was once a medical student as well. I know. 😅

Train yourself, the moment you start STEP 1, you have started thinking about STEP 4. Remember the thing I said in STEP 1 about “treating them and bringing them back to their pre-morbid status”? A good doctor does that. A good doctor TREATS THE PATIENT, NOT THE DISEASE.

The moment patient is admitted to the ward, you should anticipate everything up until the discharge plan. This is the difference between an elective admission who is discharged in the morning and an elective admission who waits until late afternoon, sometimes night, for a discharge summary. This is the difference between an emergency admission that does well and an emergency admission that does not do that well.

I know, it is easier said than done. But after reading this, I hope you have a rough idea about clerking a patient. I know I only scratch on the surface because managing a patient is not as simple as listing down the steps. You need a lot of practice, plenty of guidance and a hint of scolding in between. We all learn from mistakes, provided that we want to learn from them.

I leave you with this quote, “Medicine is science, but practising it, is an art”. Hence, you need to learn the art of clerking a patient. Similar to learning the art of presenting a case and making a referral.

There are no shortcut to it. We all learn the hard way.

Credit to: FB Aimir Ma’rof (click on the link below)